NOT I: Opening

Friday, 9 January 2026, 6 – 8 pm

-

-

Capitain Petzel is pleased to announce the group exhibition NOT I, on view from January 9, 2026.

For the staging of Not I, a monologue which lends its name to this exhibition, Samuel Beckett stripped the theater stage, creating a barren visual field, where a striking pair of red lips, a character known as Mouth, floats in total darkness. Illuminated by a single beam of light and speaking at relentless speed, the monologue is delivered by a disembodied female voice. Both a cry of terror and recognition, Not I is representative of a life glimpsed in flashes, a self seen fragmented, a memory that insists even as it slips away. It consists of associations, thematic returns and obsessive circling. The absence of linear narrative creates a manic circularity and movement without progress, pouring out involuntary memories. Mouth attempts to distance herself from recurring images and phrases heard long ago. The past resurfaces through speech that mimics the chaotic flow of recollection, where images erupt involuntarily, overlapping and repeating in an attempt to both grasp meaning and escape it.

-

Mike Kelley

City Boy – Trauma Image (from Australiana), 1984Acrylic on paper

2 parts

Paper dimensions:

106 x 106 cm / 41.7 x 41.7 inches (left)

157 x 128 cm / 61.8 x 50.4 inches (right)

Framed dimensions:

111.5 x 111 cm / 43.7 x 43.9 inches (left)

159.5 x 132 cm / 62.8 x 52 inches (right) -

The works in this exhibition approach the act of recall as something unstable. Memory’s return is involuntary and comes as a storm breaking over consciousness. The fractured nature of Beckett’s monologue mirrors this. Mouth's obsessive refusal of the “I” is the hallmark of disavowal. It is a desperate attempt to keep experience at arm’s length.

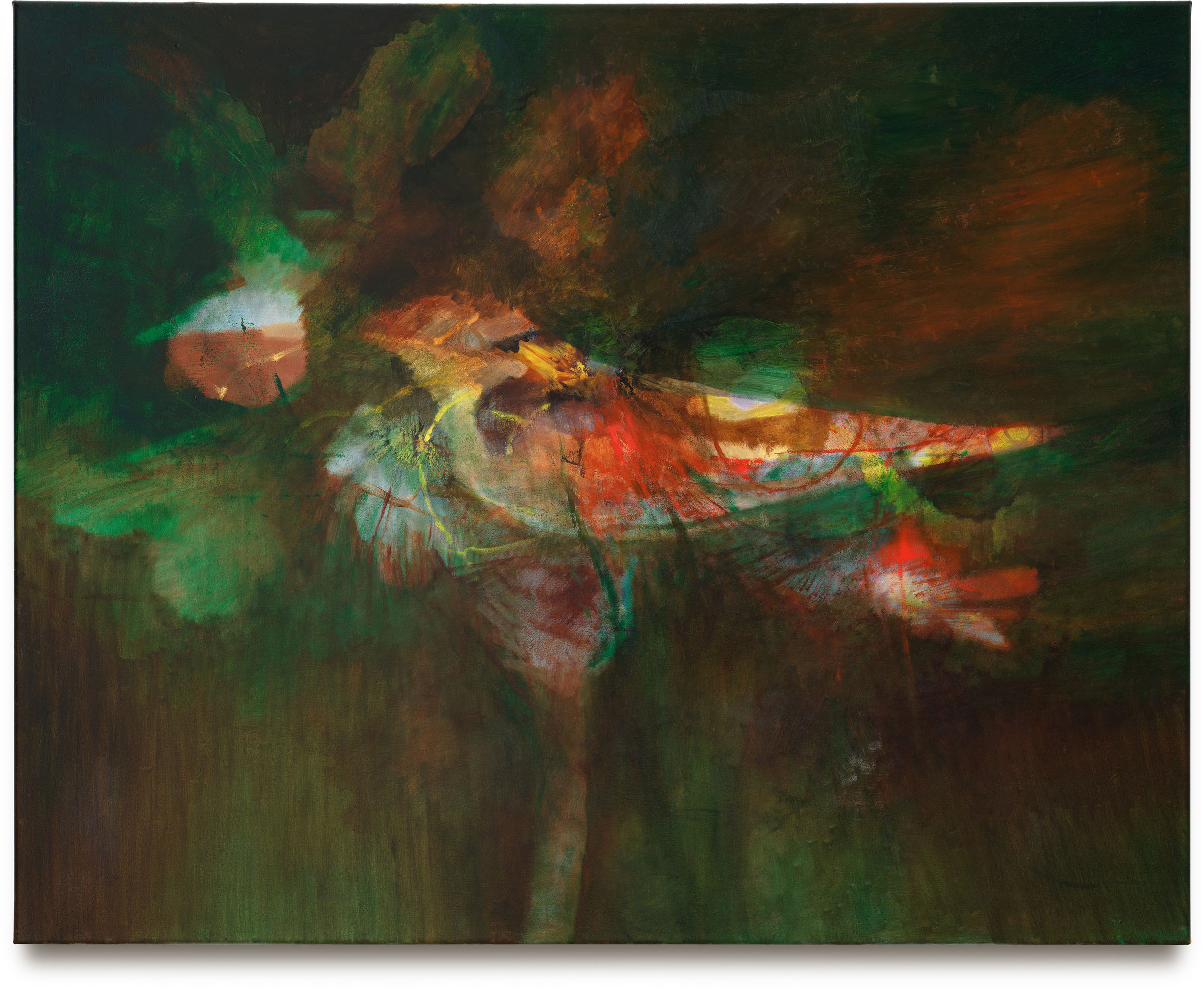

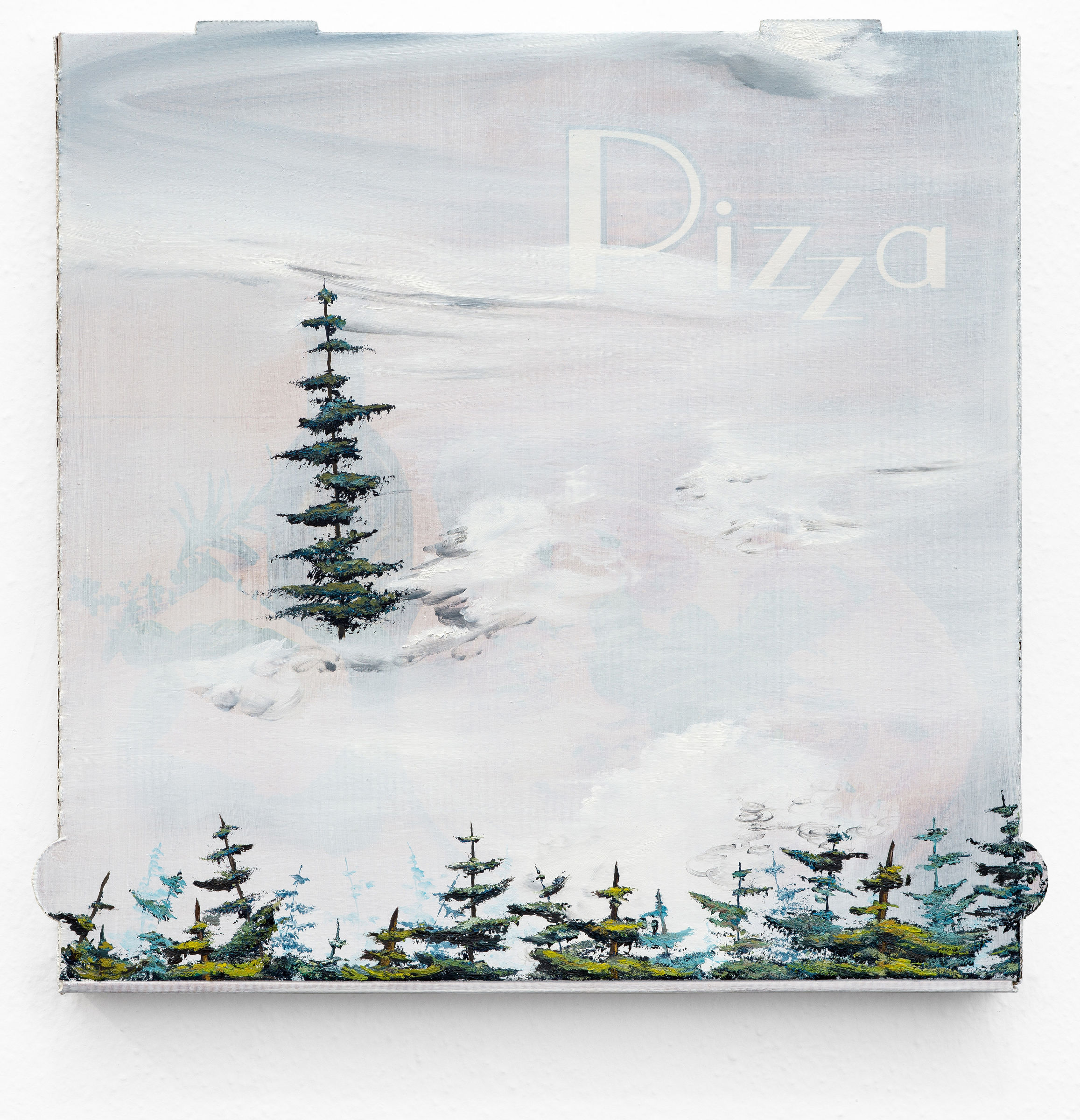

The exhibition offers a more accommodating counterpoint, in which memory’s fragments are allowed to surface. Gina Folly’s (b. 1983; Lives and works in Basel) works make this dynamic tangible, with fragile organic remnants functioning as tender residues of experience and memory. Urban Zellweger’s (b. 1991; Lives and works in Zurich) paintings transform familiar pizza boxes into blurred landscapes that echo the distortions of memory over time. Similarly, William Gaucher’s (b. 1993; Lives and works In Berlin) compositions can be seen as accumulations of painterly gestures, where traces of art-historical memory surface through layered marks. His canvases assemble residues of past images and methods into a syntax that feels familiar, echoing Beckett’s approach in which meaning emerges through the build-up of repetitions and hesitant returns.

-

-

Memory always insists, even if the self refuses to claim it. The result is a voice caught between confession and flight, compelled to articulate what it cannot acknowledge as its own – not I. This dynamic finds a powerful counterpoint in Hanne Darboven’s (b. 1941; d. 2009) Hommage an meinen Vater (Homage to my father), which approaches memory through accumulation, repetition and duration. Hand-inscribed sheets transform personal loss into a monumental system of notation, where grief is methodically repeated until it becomes a defined, visible structure.

In Beckett’s Not I, the voice is severed from the body, speaking without pause or control, an articulation driven less by intention than by compulsion. This sense of being overtaken, of speaking before understanding, finds resonance in the works in the exhibition, where forms and narratives seem to emerge from places, where the past insists. It transforms what in Beckett appears as crisis into an act of recognition, opening room for the past to return in unruly shapes. Martin Kippenberger’s (b. 1953; d. 1997) installation Jetzt geh ich in den Birkenwald, denn meine Pillen wirken bald (Now I'm going to the birch forest, because my pills will soon take effect), with its distorted birch trunks and scattered pills, stages a forest as a site of psychological disorientation, where perception buckles.

-

-

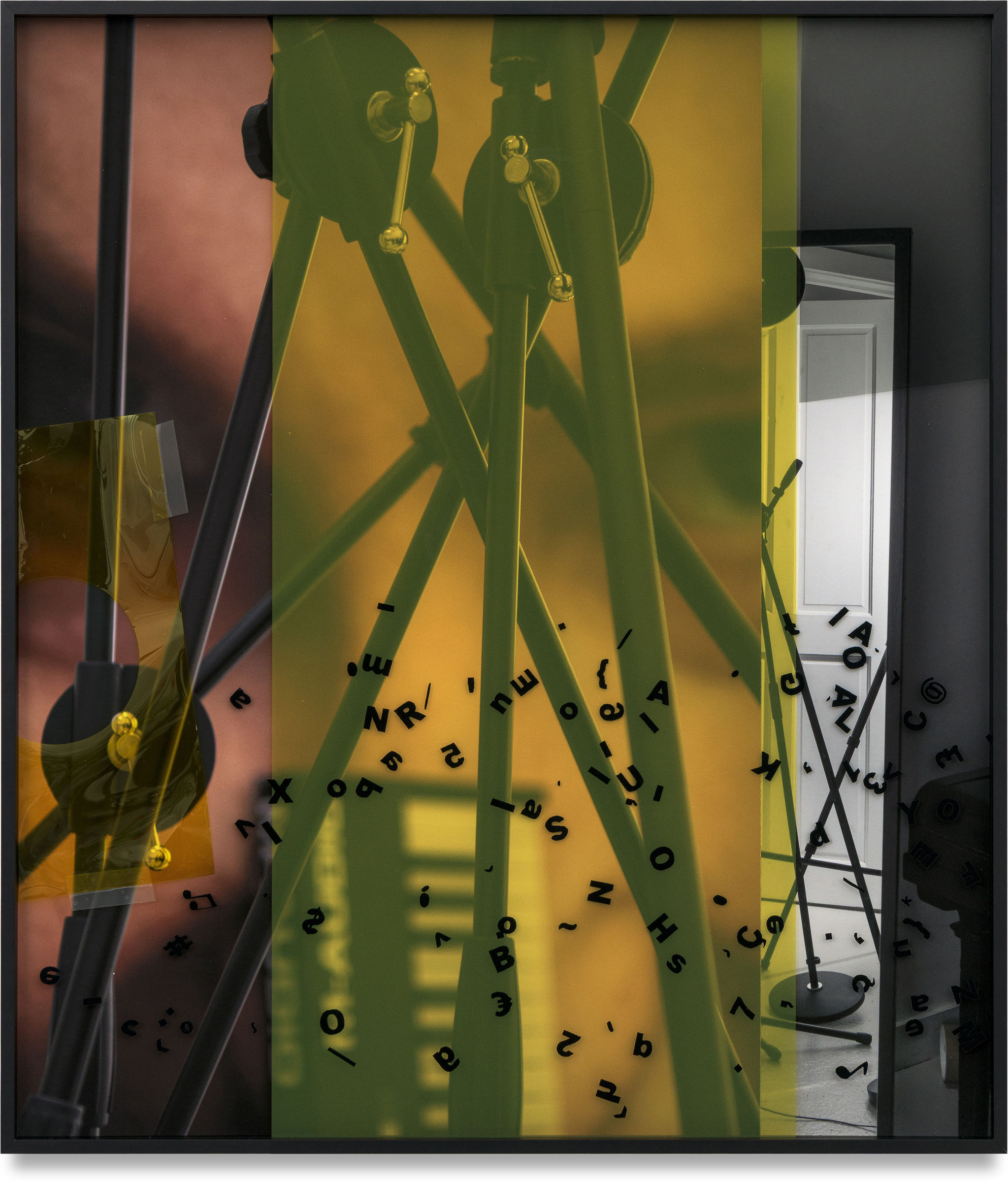

Daria Blum’s (b. 1992; Lives and works in London) photographic prints reflect instability, depicting selves that appear doubled or refracted. Xie Lei’s (b. 1983; Lives and works in Paris) painting, with its two spectral figures dissolving into one another, echoes the exhibition’s recurring sense of selves drifting, overlapping, and becoming indistinct in the currents of memory. Mike Kelley’s (b. 1954; d. 2012) Trauma Images bear a cartoon-like innocence, coupled with violent imagery and unsettling, nightmarish tension. Monika Sosnowska’s (b. 1972; Lives and works in Warsaw) Ghosts, winding metal armatures that resemble a human body, appear like the remnants of gestures or movements. Ilaria Vinci’s (b. 1991; Lives and works in Zurich) paintings, structured as onions with their concentric skins concealing an inner maze, deepen this reflection on how memory unfolds. They suggest an interiority that can only be approached through gradual peeling. The works in the exhibition trace different paths through the unstable terrain of recollection, each offering a material analogue to the fractured inner landscape Beckett renders through a solitary voice.

Tomass Aleksandrs

-

-

-

-

Request more information