Seth Price: Die Nuller Jahre

Recently I’ve been reflecting on the last ten years. It’s arbitrary, and a little absurd, like a drunk noticing the time and abruptly sobering up for an appointment: time to figure out what happened. With the turning of the decade it’s hard to avoid: these disparate years swim together, waiting to be addressed as one, whatever we end up calling it. In any case, we want to generate a series of images to replace vague and unsettled feelings, and to arrive at names. Sometimes the process of understanding artworks feels the same way.

Ten years ago I didn’t yet call myself an artist, which felt presumptuous. I wasn’t part of the art world, and I was ambivalent about calling what I did by the name art. I was making music, and producing videos that screened in short-film festivals. But I had a job working in an arts organization, and that exposed me to an entirely different conversation,one with tremendous appeal. After a few years I realized that I’d rather show my films within the art context, which offered a mode of working that seemed completely open. I came to know some other artists, and we collaborated on magazines and projects. I exhibited videos in group shows. I rented a studio. I was offered a solo show in 2004, and I decided to make sculptures. By the beginning of 2006 I had left my job. I was a professional artist then, at least as far as the government is concerned. In the four years that closed the decade, I’ve been lucky enough to have opportunities to exhibit, and to try out different forms and approaches.

This brief personal sketch is the bare outline of something often expected from artists these days, the ‘artist talk,’ where you’re invited to a school or museum to project slides of your work, discuss its development, explain yourself. It’s a contemporary form, part of the business, you could say. Through words and pictures you enter an idea of art history and context, just as surely as if you were delivering a university slide lecture on nineteenth-century painting. An artist talk supposedly lies outside the artwork, but nonetheless helps make its meaning, much like dates and titles. A production date will forever shadow your work, effecting the way it’s understood: when was this made, how does it relate to other works of the period? The artist’s words function similarly, even if they are colored by the ambiguity of persona and performance.

The video at Bortolozzi came out of a lecture I gave at a museum in 2007. I had been thinking about these questions, and I decided to videotape my talk and use the video—and the given form itself—as the basis for an artwork that might bring this strange meaning-making back into the space of exhibition, where it would feel awkward and out of place. That part worked, at least: while I’ve changed the piece constantly since 2007, bringing it far from its starting point, it still makes me nervous. When it’s exhibited alongside ‘actual’ artworks, especially pieces that appear onscreen, they feel supplemental, like props or décor. This was an interesting thing for me to confront in the intimacy of Bortolozzi’s rooms.

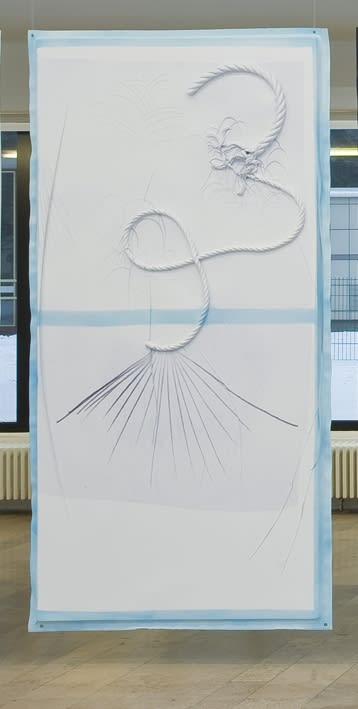

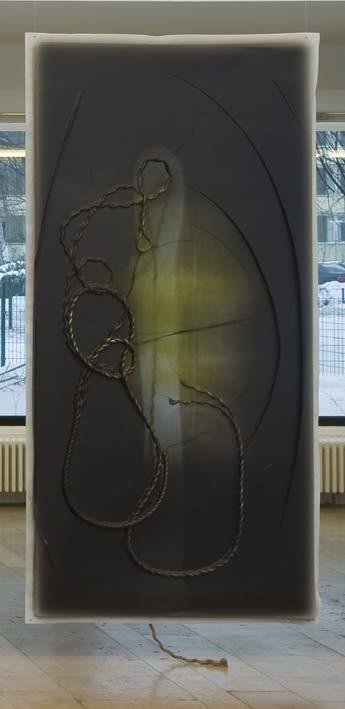

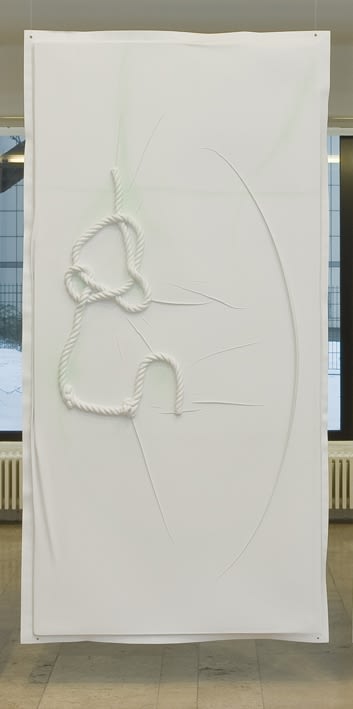

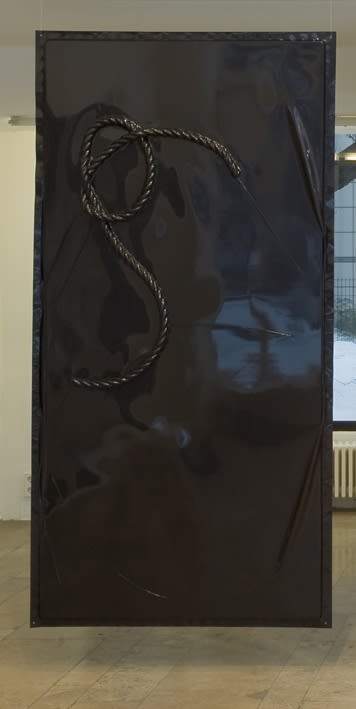

This is a very particular approach to an exhibition, in which different pieces relate to one another within a complicated gesture, but there are many other ways of thinking about how meaning is made. Exhibiting a body of work, for instance, which starts by simply stating, “here’s what I’ve been doing recently.” Maybe that’s enough. This is true of the series of works at Capitain Petzel, which share formal parameters and ideas, as well as a common title that brings them together under one reference. We know how to look at a series: one image after another, each independent but with an implicit relationship to the whole, as with an alphabet. In this show there is also the familiar movement of abstract imagery interacting with the concrete information of a title: the name completes the picture, even as it leaves a hole. These pieces come out of both gesture and industrial process, printing and painting, sculpture and image, hiding and showing, but they can’t escape the fact that a randomly placed knot will suggest readings. It is not only a gesture and a material object, but a picture and a story. Might it be possible to suggest the story of a historical decade? I wanted to yield to that impulse to be read, to generate a series ofimages that might replace vague and unsettled feelings, to arrive at names.

-

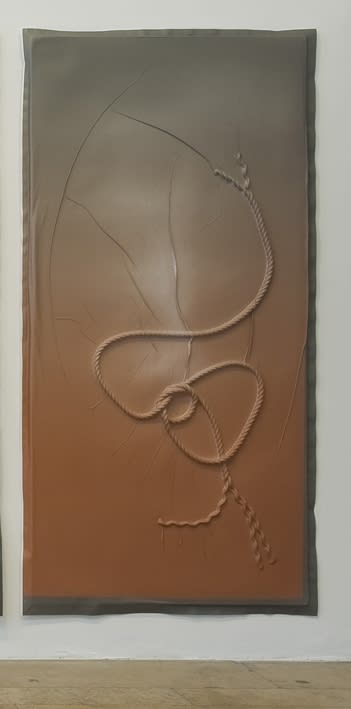

Seth PriceRapid Growth, 2009UV-cured inkjet and car enamel on high-impact polystyrene vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches

Seth PriceRapid Growth, 2009UV-cured inkjet and car enamel on high-impact polystyrene vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches -

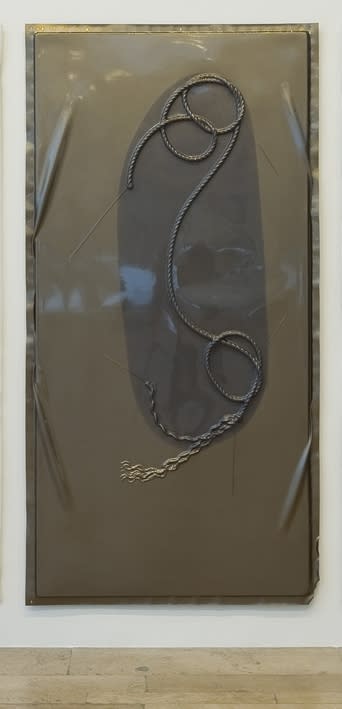

Seth PriceBig And, 2009UV-cured inkjet on high-impact polystyrene vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches

Seth PriceBig And, 2009UV-cured inkjet on high-impact polystyrene vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches -

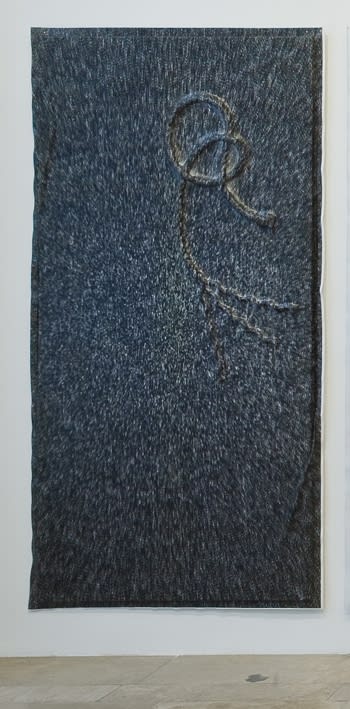

Seth PriceImportant Chair, 2009UV-cured inkjet and car enamel on PETG vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches

Seth PriceImportant Chair, 2009UV-cured inkjet and car enamel on PETG vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches -

Seth PriceSexy Dancer, 2009Car enamel and UV-cured inkjet on high-impact polystyrene vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches

Seth PriceSexy Dancer, 2009Car enamel and UV-cured inkjet on high-impact polystyrene vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches -

Seth PriceHighrise, 2009Car enamel on PETG, vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches

Seth PriceHighrise, 2009Car enamel on PETG, vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches -

Seth PriceRitual, 2009UV-cured inkjet on high-impact polystyrene vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches

Seth PriceRitual, 2009UV-cured inkjet on high-impact polystyrene vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches -

Seth PricePersonal Transportation, 2009Car enamel on PETG vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches

Seth PricePersonal Transportation, 2009Car enamel on PETG vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches -

Seth PriceGuard, 2009UV-cured inkjet and spray-enamel on high-impact polystyrene vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches

Seth PriceGuard, 2009UV-cured inkjet and spray-enamel on high-impact polystyrene vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches -

Seth PriceCornucopia, 2009Car enamel on PETG, vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches

Seth PriceCornucopia, 2009Car enamel on PETG, vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches -

Seth PriceCrazy Outlook, 2009UV-cured inkjet and car enamel on high-impact polystyrene vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches

Seth PriceCrazy Outlook, 2009UV-cured inkjet and car enamel on high-impact polystyrene vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches -

Seth PriceApparition, 2009Car enamel and UV-cured inkjet on PETG vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches

Seth PriceApparition, 2009Car enamel and UV-cured inkjet on PETG vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches -

Seth PriceCrouching and Kneeling, 2009UV-cured inkjet on high-impact polystyrene vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches

Seth PriceCrouching and Kneeling, 2009UV-cured inkjet on high-impact polystyrene vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches -

Seth PriceMedical Mask, 2009Car enamel on high-impact polystyrene vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches

Seth PriceMedical Mask, 2009Car enamel on high-impact polystyrene vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches -

Seth PriceArtist Monogram, 2009Car enamel on PETG, vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches

Seth PriceArtist Monogram, 2009Car enamel on PETG, vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches -

Seth PriceThings That Go South to North, 2009UV-cured inkjet on high-impact polystyrene vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches

Seth PriceThings That Go South to North, 2009UV-cured inkjet on high-impact polystyrene vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches -

Seth PriceHarsh Way of Life, 2009UV-cured inkjet on high-impact polystyrene vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches

Seth PriceHarsh Way of Life, 2009UV-cured inkjet on high-impact polystyrene vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches -

Seth PriceCorn Syrup, 2009Car enamel on PETG, vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches

Seth PriceCorn Syrup, 2009Car enamel on PETG, vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches -

Seth PriceSpraying, 2009Car enamel and UV-cured inkjet on PETG vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches

Seth PriceSpraying, 2009Car enamel and UV-cured inkjet on PETG vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches -

Seth PriceScreens, 2009UV-cured inkjet on high-impact polystyrene vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches

Seth PriceScreens, 2009UV-cured inkjet on high-impact polystyrene vacuum-formed over rope243.8 x 121.9 cm / 96 x 48 inches